The philosopher Dr. Friedrich Nietzsche – actually Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche, in letters also signed Fritz Nietzsche – is one of the most important thinkers of the 19th century. He is known for his criticism of religion and his remarks on nihilism. Here you can learn more about his life in a short biography, about Nietzsche’s death masks, busts, portraits, Nietzsche’s books and you can find Nietzsche quotes, worldly wisdoms and sayings.

- Friedrich Nietzsche’s Short Biography

- Nietzsche Death Mask

- Friedrich Nietzsche’s Busts

- Nietzsche busts by Max Klinger

- Nietzsche plaster bust by Siegfried Schellbach

- Nietzsche bust in marble by Max Kruse

- Friedrich Nietzsche Art Nouveau Bust by Curt Stoeving

- Friedrich Nietzsche Bust by Otto Dix

- Friedrich Nietzsche Bust by Fritz Röll

- Friedrich Nietzsche’s Portraits

- Nietzsche’s conception of art

- Quotations, Life Wisdoms, Sayings

- Nietzsche’s Books

- Read Friedrich Nietzsche Online

- References

[Photographer: Robert Züblin]

Friedrich Nietzsche’s Short Biography

Below you will find the curriculum vitae of Friedrich Nietzsche in the form of a short biography.

|

1844 1849 1856 1864 1865 ■ Nietzsche does not smoke tobacco and does not drink alcohol; however, he eats a lot of cakes and pies. 1867 1868 1869 ■ Nietzsche receives the doctoral degree from the University of Leipzig without examination and disputation, because of his publications ■ does not feel comfortable in Basel; turns down invitations; when he enters society, he maintains etiquette; is considered a ladies’ man ■ gets to know the cultural historian Jacob Burckhardt (professor of art history in Basel) personally 1870 ■ Considers devoting himself entirely to Wagner and his Bayreuth and giving up his professorship to do so ■ Applies for leave of absence from the University of Basel; wants to participate in the Franco-Prussian War as a soldier or nurse; is then a volunteer medic and collects corpses as well as wounded; falls ill: dysentery and diphtheria ■ October: returns to Basel 1871 ■ Nietzsche is ill and temporarily on leave of absence 1872 ■ Nietzsche’s The Birth of Tragedy from the Spirit of Music is published; as a result, Nietzsche’s lectures are attended less and less; already before, few students in his lectures, because Basel was not the place to study classical philology, but Berlin, Leipzig and other places; after the publication of The Birth of Tragedy from the Spirit of Music, however, Nietzsche is also dead as a man of science; in the scholars’ guild, he is scorned 1873 |

1874 ■ Nietzsche studies Max Stirner. 1876 1877 1879 ■ The search for the best climate for his illness begins. Until 1889, Nietzsche is among others in Venice, Sicily, Nice, Turin; mostly in: Genoa [winter], Sils-Maria in the Engadine [summer]. 1880 1882 ■ The Gay Science 1883 1884 1885 1886 1887 1888 1889 ■ Franz Overbeck picked Nietzsche up a few days later; Overbeck was alarmed because Nietzsche had written in a letter to Burckhardt: “At last, I would much rather be a professor in Basel than God…”; Overbeck took Nietzsche to a mental hospital in Basel, where he was picked up by his mother; finally, Nietzsche was sent to the psychiatric hospital of the University of Jena. 1890 1897 1900 ■ Cause of death: presumably paralysis of the brain due to syphilis ■ Friedrich Nietzsche’s grave is located in the old cemetery of the village church of Röcken near Leipzig, Germany ■ Name variations: Friedrich Nietzsche, later Dr Friedrich Nietzsche, actually Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche, in letters also signed “Fritz Nietzsche Dr” |

Nietzsche’s Death Mask

The myth about the death mask of Friedrich Nietzsche is said to have got a new twist only recently, when in the context of an exhibition in Basel in 2019 and 2020, “Übermensch – Friedrich Nietzsche und die Folgen” (Übermensch – Friedrich Nietzsche and the consequences), the first death mask of Friedrich Nietzsche had appeared, namely the one that had been made by Nietzsche’s cousin Adalbert Oehler 24 hours after his death. Indeed, it was known about this death mask, but whether this mask still existed, was not known until then. [1] In the literature, however, it is doubted that this mask is genuine. Rather, it is assumed that the Oehler mask is an overformation of a corrected version of the Stoeving mask. [2]

Basically, only that death mask of Friedrich Nietzsche is considered as secured authentic removed death mask, which was removed from Friedrich Nietzsche’s face by the painter and sculptor Curt Stoeving and Harry Graf Kessler two days after his death. [3] However, since this mask had a lot of flaws, such as a crooked nose and a drooping eyebrow as well as a flat, unattractively shaped beard, Nietzsche’s sister commissioned a reworking of this mask by the sculptor Rudolf Saudek, who in 1910 made the so-called Saudek mask, which stylizes a pugnacious thinker from the failed death mask of a Nietzsche marked by illness. [1] Around 1930, the sculptor Lorenz Zilken made a somewhat smoothed and partially more angular version of the Saudeck mask. [4]

The sculptor Georg Kolbe wrote a treatise on “The Making of Death Masks” and vehemently criticized any subsequent alteration to death masks: “I then no longer touch it, because it must be good. On the other hand, unfortunately, there are masks that have been reworked, even added to, – no, even worse, they have been molded, embellished. But these are absurdities, is violated, counterfeited life.” [5]

[Photographer: Ralph Hirschberger, Source: Bundesarchiv/ Wikimedia Commons, License: CC BY-SA 3.0 de]

Friedrich Nietzsche’s Busts

A large number of different busts of Friedrich Nietzsche exist, including busts by well-known sculptors and artists. Some of these busts are listed below.

Nietzsche busts by Max Klinger

There are two busts of Friedrich Nietzsche by Max Klinger. A bronze bust from 1902, which was supposed to be a correction of the failed death mask, but in the end became a fully plastic portrait bust of Friedrich Nietzsche. And a second bust that Klinger created of Nietzsche in 1903, in marble, the so-called Hermenbüste, which was ordered for the Nietzsche Archive. [6]

Nietzsche plaster bust by Siegfried Schellbach

Already in 1895, the sculptor Siegfried Schellbach had made a bust of Friedrich Nietzsche from plaster. [7] However, the bust was banished to the depot by Nietzsche’s sister, Elisabeth Förster-Nietzsche, probably because it shows Nietzsche too true-to-life. The sister wanted to present a heroic Nietzsche to the public. [8]

Nietzsche bust in marble by Max Kruse

And in 1898, Max Kruse had created a marble bust of Friedrich Nietzsche. [7]

Friedrich Nietzsche Art Nouveau Bust by Curt Stoeving

The painter and sculptor Curt Stoeving had already made a Nietzsche’s bust in 1901, and thus before Klinger, whose pedestal and remaining execution were completely in the sign of Art Nouveau. In the year 2000, this bust reappeared after it had been assumed that it had been lost. [9]

Friedrich Nietzsche Bust by Otto Dix

A caricaturistic version of the Klinger bust was produced by Otto Dix with his plaster bust of Friedrich Nietzsche from 1913/ 1914, which had a height of almost 60 cm, and was thus larger than life. [10] It is partly assumed that the bust was created in 1912, [11] with reference to the list of the Städtische Galerie Dresden. [12] With the caricaturistic depiction, Dix presumably wanted to oppose the Nietzsche cult that was practiced by parts of the reform movement “The New Weimar”, which included Nietzsche’s sister Elisabeth Förster-Nietzsche, the architect and designer Henry van de Velde and art patron Harry Graf Kessler. Starting in 1911, the latter planned a gigantic Nietzsche memorial in Weimar, a place of pilgrimage to which Nietzscheans from all over the world would come once a year. [13] However, Kessler could not realize his idea. Years later, under the National Socialists, a Nietzsche cult building was erected with the Nietzsche Memorial Hall. The first construction works had begun in 1937. [14]

On the other hand, Dix always overdrawn portraits [15], such as the protrait “Bildnis der Tänzerin Anita Berber”, in which he had depicted the dancer Anita Berber – half-sister of the ceramist Hans Berber-Credner – as an aging woman.

The Dix bust was painted dark green. Art historian Dr Barbara Orelli-Messerli assumes that Dix wanted to imitate the patina of a bronze figure by painting it dark green. The art historian Olaf Peters sees in the use of green as a colour an allusion to a passage in Nietzsche’s book “Die fröhliche Wissenschaft” [16]:

“Will and wave. – How greedily this wave approaches, as if it had something to achieve! How it creeps with frightening haste into the innermost corners of the rocky clefts! It seems that it wants to get ahead of someone; it seems that something is hidden there that has value, great value. – And now she comes back, a little slower, still white with excitement, – is she disappointed? Has she found what she was looking for? Is she disappointed? – But already another wave is approaching, greedier and wilder than the first, and its soul, too, seems to be full of secrets and the desire to dig up treasure. This is how the waves live, – this is how we, the willing, live! – I will say no more. – So? You distrust me? You are angry with me, you beautiful beasts? Are you afraid that I will betray your secret completely? Well! Be angry with me, raise your green dangerous bodies as high as you can, make a wall between me and the sun – just like now! Verily, already nothing is left of the world but green twilight and green lightning. Do as you will, you wanton ones, roar with lust and malice – or dive down again, pour your emeralds down into the deepest depths, throw away your endless white shag of foam and spray over it – it is all right with me, for everything suits you so well, and I am so good to you for everything: how will I betray you! For – hear it well! – I know you and your secret, I know your sex! You and I are of one family! – You and I, we have one secret!”

(Die fröhliche Wissenschaft (“la gaya scienza”), 1882: § 310)

Olaf Peters’ interpretation that the green colouring is an “iconological attribution of meaning” [17] is convincing insofar as the quoted passage from “Die fröhliche Wissenschaft” not only speaks of the colour green, but also of “wave” and “rocky clefts”. The slanting protrusion of the head of Dix’s Nietzsche bust can indeed also be interpreted as a wave and the fissured torso of the bust as rocky clefts.

Dix had been intensively studying philosophical works by Nietzsche since 1911, especially “Die fröhliche Wissenschaft” and “Also sprach Zarathustra”. [18] It is therefore quite plausible that Dix knew the quoted passage from “Die fröhliche Wissenschaft” well. Dix once said of Nietzsche’s philosophy, “That was the only correct philosophy.” [19] The lithograph “Der Gekreuzigte” from 1969, which is an allusion to Nietzsche’s suffering, was one of Dix’s last works, making clear the importance of Nietzsche in Dix’s life. [20] Apart from the Nietzsche sculpture, Dix made no other sculptural works in his life.

In the early 1920s, Dix’s Nietzsche sculpture was purchased by the Dresden City Museum.

In 1937, the bust of Nietzsche made by Otto Dix was confiscated by the Nazis because they considered it “degenerate art.” [18] During transport to Berlin, it is said to have arrived there damaged in 1938. [21] It was subsequently sold in Switzerland in 1939 by the Galerie Fischer (Lucerne) as lot 35 among other works by Otto Dix with the description “Nietzsche. Expressive portrait head of the German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche. Plaster, painted green, 58/48 cm. See fig. p. 21. Dresden, Stadtmuseum” allegedly sold at auction. The auction was titled “Paintings and Sculptures of Modern Masters. From German Museums.” [22] Art historian Dr. Barbara Orelli-Messerli writes in this regard that according to the price reports of the Fischer Gallery, the Dix bust was said to have sold at this auction for 4200 Swiss francs, with no indication of the purchaser. Orelli-Messerli further writes that the sale list of the auction has many blanks, from which she concludes that the information of the Fischer Gallery did not correspond to what actually happened. The art historian further concludes that the Dix-Nietzsche bust went back to Germany to the Nazis and their art dealers. According to Orelli-Messerli, only the painting by Dix “The Artist’s Parents” would have actually found a buyer among the four Dix works at the auction of the Fischer Gallery, namely the Kunstmuseum Basel. [23] Since the supposed return from the Fischer auction to Germany, the trace of Dix’s Nietzsche bust is lost. Today, the bust is considered lost. [18]

Dix was very sad about the loss of his Nietzsche’s bust. He had even considered making a new version of the Nietzsche’s bust. [24]

Friedrich Nietzsche by Fritz Röll in the Nietzsche Archive

The sculptor Fritz Röll also made a Nietzsche bust, in 1921, which was exhibited in the Nietzsche Archive.

Friedrich Nietzsche’s Portraits

There are also different portraits of Friedrich Nietzsche, for example in the form of drawings or paintings. For example, besides two oil paintings (1906) with the title “Friedrich Nietzsche” by the painter Edvard Munch, in which the motif is the same, but the execution is somewhat different, there is also a similar version as a drawing, made with charcoal, tempera and pastel on paper (1905). In addition, Munch made a lithograph of Nietzsche, of which there are several prints.

Munch also made other drawings of Nietzsche, such as “Friedrich Nietzsche sitting in his room” with colored chalk and ink on cardboard (1905). For this drawing, he was inspired by the famous portrait photograph that the portrait painter and photographer Gustav Adolf Schultze had made of Nietzsche in 1882.

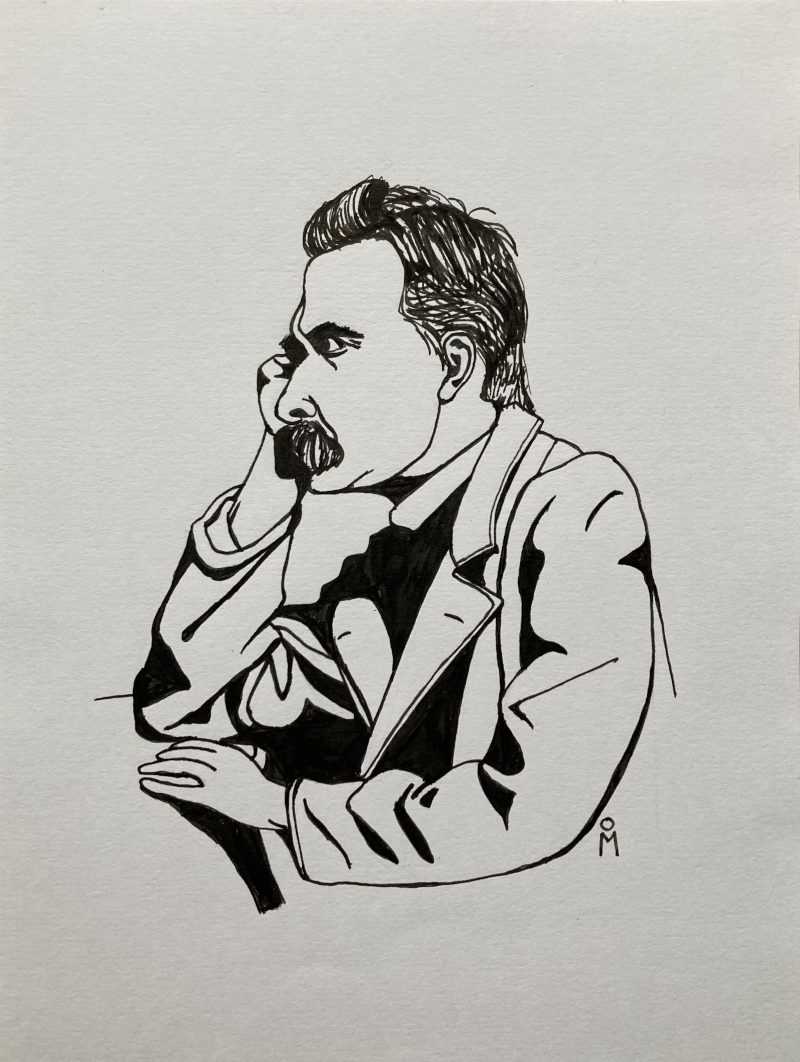

Mila Vázquez Otero (* 1978) –

Portrait of Friedrich Nietzsche

(drawing in ink, inspired by the

Portrait photo of Gustav Adolf Schultze)

140,00 €

incl. shipping

Delivery time: 7-14 days

To the offer

Nietzsche’s conception of art

Friedrich Nietzsche’s view of art contradicted that of the mainstream of the time and still contradicts the view of art prevalent in large sections of society today. In particular, Nietzsche did not share the opinion of the well-known archaeologist Johann Joachim Winckelmann that Greek works should be imitated. Rather, Nietzsche assumed that the ideal of beauty is shaped by the circumstances of the time [25]:

“Beauty according to the age. – If our sculptors, painters and musicians want to meet the sense of the time, they must form beauty in a dull, gigantic and nervous way: just as the Greeks, under the spell of their morality of moderation, saw and formed beauty as Apollo from the Belvedere. We should actually call him ugly! But the silly ‘classicists’ have deprived us of all honesty!”

(Morgenröthe, Thoughts on Moral Prejudices, 1881: § 161)

“Increase of beauty. – Why does beauty increase with civilisation? Because in civilised man the three occasions for ugliness come seldom and ever more seldom: first, the affections in their wildest outbreaks; second, the physical exertions of the utmost degree; third, the necessity of instilling fear by sight, which is so great and frequent on lower and endangered stages of culture that it itself establishes gestures and ceremonial and makes ugliness a duty.”

(Morgenröthe, Thoughts on Moral Prejudices, 1881: § 515)

With his conception of art, Nietzsche at the same time turned against the mathematisation of the beautiful by adopting the ancient ideal of beauty, which is characterised by measurements and proportions. This mathematical standardisation – which is actually an antique standardisation – is still current today, namely through the fixation on breast, waist and hip circumference to describe, in particular, the female figure as a model. [25]

Friedrich Nietzsche Quotes, Life Wisdoms and Sayings

There are a lot of quotes from Friedrich Nietzsche. Here is a selection of Nietzsche quotes but also of Nietzsche worldly wisdoms and Nietzsche sayings with sources:

“You wage war? You are afraid of a neighbor? Then take away the boundary stones – so you no longer have a neighbor.”

(From the estate, November 1882 to February 1883)

▬

“Without music, life would be a mistake.”

(Twilight of the Idols, or, How to Philosophize with a Hammer, 1889)

▬

“What, in the last analysis, are the truths of man? – They are the irrefutable errors of man.”

(The Gay Science (“la gaya scienza”), 1882)

▬

“Something may be irrefutable: therefore it is not yet true.”

(From the estate, spring 1884 to fall 1885)

▬

“Life is worth living, says art, the most beautiful seductress; life is worth knowing, says science.”

(Homer and classical philology, 1869)

▬

“One must still have chaos within oneself to be able to give birth to a dancing star.”

(Thus Spoke Zarathustra – A Book for All and None, 1883)

▬

“Every word is a prejudice.”

(Human, All Too Human: A Book for Free Spirits, 1878-1880)

▬

“All men, as at all times, so also now, break down into slaves and free men; for he who has not two-thirds of his day for himself is a slave, be he, by the way, who he will: statesman, merchant, official, scholar.”

(Human, All Too Human: A Book for Free Spirits, 1878-1880)

▬

“[…]; my doctrine that the world of good and evil is only an apparent and perspective world is such an innovation that it sometimes makes me lose hearing and sight.”

(Letter from Friedrich Nietzsche to Franz Overbeck, 23.2.1884)

▬

“In some remote corner of the universe flickeringly poured out in countless solar systems, there was once a star on which clever animals invented recognition. It was the most haughty and most mendacious minute of the ‘world history’: but nevertheless only one minute. After a few breaths of nature the star froze, and the clever animals had to die.”

(On Truth and Lies in a Nonmoral Sense, 1873)

Nietzsche’s Books

Here I list the books by Friedrich Nietzsche, listing first the Friedrich Nietzsche works with philosophical themes.

Philosophical Works by Friedrich Nietzsche

- Five Prefaces to Five Unwritten Books, 1872

I. On the Pathos of Truth

II. On the Future of Our Educational Institutions

III. The Greek State

IV. The Relation Between a Schopenhauerian Philosophy and a German Culture

V. Homer’s Contest - The Birth of Tragedy from the Spirit of Music, 1872

- On Truth and Lies in a Nonmoral Sense, 1873

- Philosophy in the Tragic Age of the Greeks, 1873

- Untimely Meditations, 1873-1876

– David Strauss, the Confessor and the Writer, 1873

– On the Advantage and Disadvantage of History for Life, 1874

– Schopenhauer as Educator, 1874

– Richard Wagner in Bayreuth, 1876 - Human, All Too Human: A Book for Free Spirits, 1878-1880

- The Wanderer and His Shadow (Der Wanderer und sein Schatten), 1880

- The Dawn of Day, 1881

- Idylls from Messina, 1882

- The Gay Science (“la gaya scienza”), 1882

- Thus Spoke Zarathustra – A Book for All and None, 1883

- Beyond Good and Evil – Prelude to a Philosophy of the Future, 1886

- On the Genealogy of Morality: A Polemic, 1887

- The Case of Wagner, 1888

- Dionysus Dithyrambs, 1889

- Twilight of the Idols, or, How to Philosophize with a Hammer, 1889

- The Antichrist, 1895

- Nietzsche contra Wagner; Out of the Files of a Psychologist, 1895

- Ecce Homo: How One Becomes What One Is, 1888

Interpretation aids for Nietzsche’s works

In the following I list interpretation aids to Nietzsche’s works:

- Nietzsches Zarathustra, Mystiker des Nihilismus: Eine Interpretation von Friedrich Nietzsches “Also sprach Zarathustra. Ein Buch für Alle und Keinen”, from Roland Duhamel

| Duhamel, Roland: |

| Nietzsches Zarathustra, Mystike.. |

|

| order at eurobuch.com |

Books about Nietzsche

Here I list books that were written about Nietzsche, respectively, in which important remarks about Nietzsche were made:

- Friedrich Nietzsche in seinen Werken, biography by Lou von Andreas-Salomé (first publication: 1894)

- When Nietzsche Wept, novel by Irvin D. Yalom (first publication: 1992)

Movies about Nietzsche

Here I list films in which Friedrich Nietzsche plays an important role:

- When Nietzsche Wept (first release: 2007), based on the novel of the same name by Irvin D. Yalom

- The Turin Horse (Original title: A torinói ló) (first release: 2011), written by László Krasznahorkai, Béla Tarr

Read Friedrich Nietzsche Online

If you want to read Friedrich Nietzsche online, you can do so at Project Gutenberg. There you can read many of Nietzsche’s published books, as well as his posthumous fragments and poems.

Furthermore, you can read Nietzsche online at the following sites:

- Friedrich Nietzsche, “Digitale Kritische Gesamtausgabe, Werke und Briefe”: www.nietzschesource.org/#eKGWB

- Friedrich Nietzsche, “Digital Facsimile Complete Edition”: www.nietzschesource.org/DFGA

The page “Friedrich Nietzsche, ‘Digitale Kritische Gesamtausgabe, Werke und Briefe'” (www.nietzschesource.org/#eKGWB) is an excellent place to search for text passages using search terms or entire sentences.

References

[1] Nietzsche-Totenmaske wiederentdeckt. Der Krieger und der Kranke, Tagesspiegel, 24.11.2019.

[2] Lorenz, Ulrike/ Valk Kult, Thorsten: Kult – Kunst – Kapital. Das Nietzsche-Archiv und die Moderne um 1900. Klassik Stiftung Weimar. Yearbook 2020, Göttingen 2020, p. 288.

[3] Hertl, Michael: Der Mythos Friedrich Nietzsche und seine Totenmasken. Optische Manifeste seines Kults und Bildzitate in der Kunst, Würzburg 2007.

[4] Lorenz, Ulrike und Valk Kult, Thorsten: Kult – Kunst – Kapital. Das Nietzsche-Archiv und die Moderne um 1900. Klassik Stiftung Weimar. Yearbook 2020, Göttingen 2020, p. 292.

[5] Georg Kolbe: Das Abnehmen von Totenmasken, S. XLIII, in: Ernst Benkard (ed.): Das ewige Antlitz. Eine Sammlung von Totenmasken, Berlin 1927.

[6] Die Klinger-Büste. Wie Max Klinger aus einer misslungenen Totenmaske das wohl berühmteste Nietzsche-Abbild für die Ewigkeit formte, Klassik Stiftung Weimar.

[7] Olaf Peters: Otto Dix: Der unerschrockene Blick. Eine Biographie, Stuttgart 2013.

[8] Goethe-Schiller-Archiv Weimar: Aus der Denkerwerkstatt, Mitteldeutsche Zeitung, 23.09.2014.

[9] Lorenz, Ulrike und Valk Kult, Thorsten: Kult – Kunst – Kapital. Das Nietzsche-Archiv und die Moderne um 1900. Klassik Stiftung Weimar. Yearbook 2020, Göttingen 2020, p. 286.

[10] Dietrich Schubert: »DIX avant DIX« Das Jugend- und Frühwerk 1903-1914, published by Ulrike Lorenz Besprechung der Ausstellung im Kunstmuseum Gera, Orangerie (12. November 2000 till 28. Januar 2001, anschließend in der Städt. Galerie Albstadt), in kritische berichte 2/01, p. 78.

[16] Peters, Olaf: Der unerschrockene Blick, Eine Biographie, Stuttgart 2013, pp. 34-35.

[17] Peters, Olaf: Der unerschrockenene Blick, Eine Biographie, Stuttgart 2013, p. 35.

[18] Peters, Olaf (ed.): Otto Dix, München, Berlin, London, New York 2011, pp. 16-17.

[19] Schmidt, Diether: Otto Dix im Selbstbildnis, Berlin 1978, p. 280.

[22] Paintings and sculptures by modern masters. From German museums. Auction in Lucerne. On 30 June 1939. Gallery Fischer, Lucerne.

[23] von Orelli-Messerli, Barbara: Otto Dix – der Künstler, der alles sehen wollte. The View of Suffering and Pleasure in the New Objectivity, in: conexus 1/2018, pp. 83-84.

[24] Renate Müller-Buck: Der Gekreuzigte, in: Renate Reschke, Marco Brusotti (eds.): “Einige werden posthum geboren”. Friedrich Nietzsches Wirkungen, Berlin, Boston 2012, p. 254.

[25] Macho, Thomas: Die Regel und die Ausnahme. Zur Kanonisierbarkeit des Schönen, in: Sachs, Melanie/ Sander, Sabine (eds.): Die Permanenz des Ästhetischen, Wiesbaden 2009, p. 131.

Ross, Werner: Der ängstliche Adler. Friedrich Nietzsches Leben, München 1990.

Safranski, Rüdiger: Nietzsche. Biographie seines Denkens, München 2000.