Bauhaus Pottery

Many people are fascinated by the so-called Bauhaus pottery. But what is it about Bahaus pottery and what is Bauhaus style? You have to distinguish between Bauhaus as a place of origin and Bauhaus as a style, also known as Bauhaus design.

The national Bauhaus was founded in 1919 as a school for applied arts in Weimar. Art and craft were to be reunited, with founder and architect Walter Gropius seeing construction as the ultimate goal of “all visual activity,” as stated in the manifesto and program of the Weimar State Bauhaus. Through the unified consideration of art and craft, students were to learn both design and craft skills. [1] The idea behind this was that there was no such thing as “art by trade,” but that the artist was only an “enhancement of the craftsman.” The method in the Bauhaus Manifesto is: “Reunification of all work-art disciplines – sculpture, painting, applied arts and crafts – into a new art of building as its indissoluble components.” Because of the emphasis on craftsmanship, the terms master, journeyman, and apprentice were used instead of teacher and student to refer to members of the Bauhaus. [2]

Today, the term Bauhaus is often used to describe a style (Bauhaus style or Bauhaus design) that uses the primary Bauhaus shapes of circle, square and triangle, as well as the primary Bauhaus colours of blue, red and yellow. To highlight the great influence of the Bauhaus style on modern architecture and design, one often speaks of the Bauhaus movement.

(because of the Bauhaus primary form

circle) and presumably in terms of

origin (since it probably came from a

former Bauhaus workshop, i.e.

Otto Lindig’s workshop in Dornburg)

History of the new art school

The Bauhaus Pottery in Dornburg

Exams rules Bauhaus pottery workshop

After end of Bauhaus in Weimar

“Laboratory for industry”

The masters of the Bauhaus

List of Bauhaus students

Sources

Bauhaus Pottery Works

History of the new art school

Due to a shift to the right in the Thuringian state elections in 1924, the State Bauhaus was expelled from Weimar. But by 1925, the Bauhaus was able to find refuge in Dessau, Anhalt, and was now called “Bauhaus Dessau – Hochschule für Gestaltung.” The new building designed by Walter Gropius was opened in 1926. In 1932, the Bauhaus was expelled by the political right here as well. The last Bauhaus director, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, then reopened the school in the same year for one semester as a private institution; this time in Berlin-Lankwitz in the former telephone factory Tefag (Birkbuschstraße 49). In 1933, however, the Bauhaus came to an end in Berlin as well.

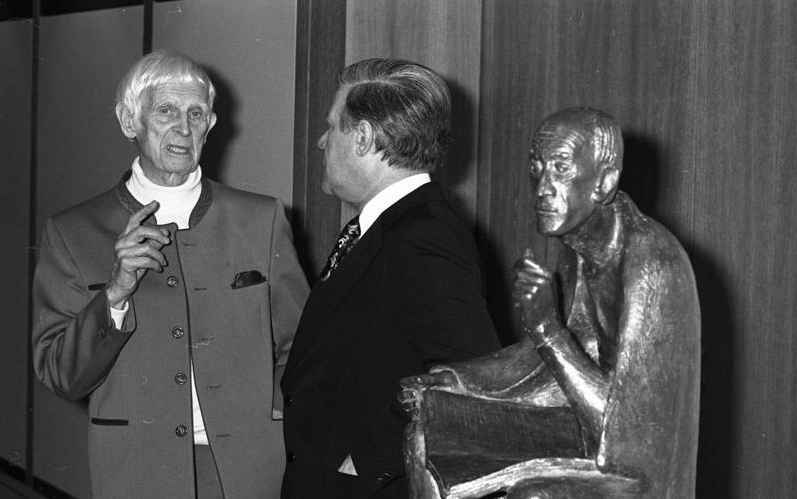

Photo: Robert Züblin

The Bauhaus Pottery in Dornburg

After the founding of the Bauhaus, its ceramics department was set up in a room of the Schmidt kiln factory in Weimar. There, the Bauhäusler initially wanted to concentrate on building ceramics. Since the cooperation with the kiln factory ended already at the beginning of 1920, the ceramic training of the Bauhaus students was transferred to the Krehan brothers’ pottery in Dornburg, where they could now also deal with utility ceramics. It was a classic win-win situation: the Krehan pottery had fallen on economic hard times and the Bauhaus ceramics department needed a new training centre. [3]

The Krehan pottery produced – also during the Bauhaus period – typical ceramics in the Bürgel tradition. It produced utilitarian ceramics, including earthenware with lead glazes and engobe as well as stoneware with salt glazes. [4]

In 1921, the new Bauhaus workshop in Dornburg was able to start work under its form master, the sculptor Gerhard Marcks, and form experiments in vessel production were carried out. In these early days, functionality was almost ignored. The spouts of jugs, for example, were overlong or had thin handles; untouchable for everyday use. Sometimes these experiments were carried out jointly by Lindig, Bogler and Marcks. Gropius downgraded this artistic creation of one-offs as “romantic production”. Nevertheless, these experiments were the basis for the models “that corresponded to his idea of craftsmanship as a laboratory for industry and were created for or as a result of the Bauhaus exhibition in 1923. Imaginative, aesthetically sophisticated and variable, they allowed for different types of vessels with a basic stock of prefabricated elements.” [5]

[Photographer: unknown, Source: Bundesarchiv/ Wikimedia Commons, Licence: CC BY-SA 3.0 de]

The initial phase of experimentation also saw the creation of Theodor Bogler’s combination teapot, which has become a Bauhaus symbol and which many see as the epitome of Bauhaus pottery because of its angularity and thus its reference to the Bauhaus primary shape “square”. Otto Lindig also created vessels with interchangeable parts, which allowed the function of the object to be changed depending on how it was assembled. [6] Lindig and Bogler were open to the turn towards industry and machinery as demanded by Gropius. The Bauhaus founder’s goal: “to make … accomplished work accessible to more people.” [7] Werkmeister Krehan wanted to hold on to the “romantic mode of production” of the classical potter’s craft. [8] Marcks tried to convince those involved to at least hold on to the craft as the basis of artistic creation. By focusing on industrial production, he saw the danger that a displacement of craft training would take place. [9]

Bauhaus pottery did not spread en masse in its own time either. It is true that in the end there was serial production in the Dornburg Bauhaus pottery; but on a very small scale, given the chronically limited resources of the Bauhaus workshop. The production of the Dornburg pieces in the factories of the established ceramics and porcelain industry also did not go beyond isolated pieces. At least the ceramic Bauhaus department in Dornburg was the first among the Bauhaus workshops to establish serious contacts with industry at an early stage. [10] In 1924/ 25, there was also a licensed production of spice jars, bowls and cup vases by a pottery in Bürgel. [11]

Examination regulations of the Bauhaus pottery workshop

Education in Bauhaus pottery was taken up by only a few people and completed by even fewer. Of the students at the Bauhaus pottery workshop, only four ended up taking the journeyman’s examination: Otto Lindig, Theo Bogler and Marguerite Friedlaender in 1922, as well as Werner Burri in 1924.”[12]

The examination regulations for the Bauhaus pottery workshop were closely based on the requirements of the traditional pottery trades (the Bauhaus wanted to counteract the scepticism of the long-established craftsmen) [13]:

“1. working the clay

2. building up the clay vessels and pieces of clay for firing

a. Turning pots on the wheel and handles

b. Building up brick sculpture (building sculpture), pressing out the plaster mould

c. Kiln building (tiles)

d. Turning plaster moulds

3. glazing, pouring, painting according to different techniques (painting horn, scratching, etc.)

4. firing in the kiln (open firing, capsule firing), heating and regulating the temperature

5. prior knowledge of chemistry for the composition of glazes

6. knowledge of tools, price calculations and bookkeeping, technical literature.”

After the end of the Bauhaus in Weimar

In 1924, the material difficulties at the Bauhaus pottery in Dornburg meant that orders could no longer be fulfilled. Lindig therefore suggested either returning to purely artisanal production, i.e. dispensing with serial production altogether, or converting the workshop into a ceramics factory. [14] In the end, no decision was made, because the Bauhaus in Weimar had to move to Dessau in Anhalt; the Dornburg workshop was not taken with it.

Gerhard Marcks describes the fate of the Bauhaus pottery after the demise of the Bauhaus thus:

“When the Weimar Bauhaus blew up, the pottery split – one branch went to Halle – Lindig was left alone in Dornburg. The reputation of the Bauhaus pottery was cemented and endured through decades of cloistered solitude – at the Leipzig Fair they met up with other Bauhäusler who were now scattered all over Germany.” [15]

Lindig and Burri stayed in Dornburg, while Marcks, Friedlaender and Franz Wildenhain went to the Burg Giebichenstein School of Arts and Crafts in Halle. Marcks was visibly relieved to leave Dornburg. In the end, the Bauhaus pottery had no longer interested him; moreover, he had been overtaxed, as he himself wrote. “[…] the young journeymen wanted to have the fame for themselves and were not very honourable about it. I stepped aside because I wanted to let them develop freely, but they secretly kicked me in the back a little. And of course, the one who owed me the most, the most stupid.” [16] He reports tragic events: “Mrs. B. [Bogler] took her own life. All sorts of things have gone on in this rose paradise.” [17] Not to forget the precarious spatial situation in Dornburg, because of which Marcks appealed to the Bauhaus in drastic words as early as 1923: “I contracted a kidney affection in my previous workshop during the winter, so I ask and present the Bauhaus with the alternative: new workshop or borrowed coffin.” [18]

After the Bauhaus moved, the Dornburg pottery was taken over by its successor, the Weimar Hochschule für Handwerk und Baukunst; under the direction of Otto Lindig. The Bauhaus had not opened a ceramics department in Dessau. Lindig’s students of that time included: Ernst Brandenburg, Johannes Leßmann, Egon Bregger, Wieland Tröschel and Leopold Berghold: in later times also Ingrid Triller (née Abenius), Erich Triller, Walburga Külz, Rose Krebs and Marieluise Fischer. In 1930, after the rise of the first German Nazi government in Weimar, the Weimar College of Crafts and Architecture had also fallen into Nazi hands and a collaboration with the Dornburg workshop had ended. Lindig finally leased the pottery in the same year. [19]

[Photo: Thomas Lehmann, source: Bundesarchiv/ Wikimedia Commons, licence: CC BY-SA 3.0 de]

The Bauhaus develops into a “laboratory for industry”

Whereas in the beginning the aim was to unite art and craft, in the end the Bauhaus goal was industrial design. Marck’s disappointment with the new objectives set by Gropius began very early, when he wrote from faraway Dornburg in June 1921: “I can no longer agree with the Bauhaus at all. Gropius is pure Wilhelm II, and sooner or later the car is stuck in the mud of formalism. Every four weeks I contemplate my abdication in my dear heart. If I were still in Weimar, I would no longer be at the B.-” [20]

The differences between Marcks (art)/ Krehan (craft) and Lindig/ Bogler (industrial production) were thus characteristic of the Bauhaus in general. In Marcks’ eyes, the constructivist Lazlo Moholy-Nagy was the main culprit of this development; he had been the “gravedigger of the Bauhaus”; [21] instead of putting a stop to Moholy’s influence, Gropius had “betrayed the muse to Moholy & Co.” [22]

In addition to the anti-art formalism oriented towards the best possible industrial production, Marcks also criticised theorising. [23] He made his position clear as early as 1922: “One cannot derive a world view from the pros and cons of mechanical aesthetics. The machine cannot be denied, nor can it be overestimated. Give it what is its own. Today, of course, one will drive a train and use a typewriter, but one will hardly ever write a love letter or a letter to Father Christmas with a machine. So if you don’t reject mechanical aesthetics, but embrace them, then go to work with an open mind. The machine form has long since been found, and by engineers who may also have been artists; for artist is not a question of profession. It is just as wrong to impose foreign elements on the building or the machine as style-forming (Ionic column or square) as it is empty aestheticism to form machine-like non-machines. […] Whoever, therefore, wants to help the engineers, blacksmiths, potters, carpenters, etc., should become one himself, i.e. immerse himself in the object and not in theory.” [24]

It is true that the form master Marcks gave his pupils a free hand in Dornburg, as he himself wrote [25]. Nevertheless, he had an influence, as Bauhaus expert Dr Klaus Weber suspects. On the one hand, Marcks taught his pupils “to design their vessels primarily as sculptural objects whose components are clearly set off from one another, but are nevertheless connected to form an organically cohesive whole.” [26] On the other hand, he also passed on his “knowledge of non-European as well as Mediterranean and ancient vessel forms”, “the influence of which can be clearly seen in some of Lindig’s or Bogler’s early works, where it sometimes forms peculiar syntheses with traditional forms of Thuringian pottery”. [27]

Otto Lindig estimated the formal influence of his master Marcks to be slight: “His influence, which had a great effect, was based exclusively on conversation with him, on the fact that he allowed us to take part in his work, that we all lived together completely freely and open-mindedly.” [28] The personal togetherness is also emphasised by Marcks in his memoirs: “The whole pottery, suspected by the peasants as ‘communism’ (the blond brother Krehan took revenge for this: ‘cheating a peasant is no sin’), was a family.” [29]

The masters of the Bauhaus (not exhaustive)

To emphasise modern teaching methods, Walter Gropius introduced new terminology for the teaching staff: “form masters” were the names of teachers who taught artistic (design) methods; “work masters” were the names of those teachers who taught a craft. [30] The form masters who moved to Dessau in 1926 were given the title “professors”. Specifically, this applied to Feininger, Kandinsky, Klee, Moholy-Nagy, Muche and Schlemmer. [31]

Nude and figure drawing:

Max Thedy (master of form) [e]

Oskar Schlemmer (master of form) [e]

Joost Schmidt (junior master) [e]

Architecture:

Hannes Meyer (junior master and Bauhaus Director 1928-1930) [e].

Adolf Meyer (teacher)

Construction:

Hans Wittwer (teacher) [e]

Building apprenticeship:

Hannes Meyer (junior master and Bauhaus Director 1928-1930) [e]

Carl Fieger (teacher) [e]

Hans Wittwer (teacher) [e]

Anton Brenner (teacher) [e]

Ludwig Mies van der Rohe (teacher and Bauhaus director 1930-1933) [e]

[Photo: Georg Pahl, source: Bundesarchiv/ Wikimedia Commons, licence: CC BY-SA 3.0 de]

Building and Planning, Urban Planning and Settlement:

Ludwig Hilberseimer (teacher) [e]

Ludwig Mies van der Rohe (teacher and Bauhaus director 1930-1933) [e]

Mart Stam (teacher) [e]

Visual form theory:

Paul Klee (master of form) [e]

Stage:

Lothar Schreyer (teacher) [e]

Oskar Schlemmer (master of form) [e]

Bookbinding:

Georg Muche (master of form) [e]

Paul Klee (master of formr) [e]

Lothar Schreyer (master of form) [e]

Otto Dorfner (foreman) [e]

Printers:

Walter Klemm (master of form) [e]

Lyonel Feininger (master of form) [e]

Carl Zaubitzer (foreman) [e]

Form and colour theory:

Wassily Kandinsky (master of form) [e]

Photography:

Walter Peterhans (teacher/work master) [e]

Stained glass:

Johannes Itten (master of form) [e]

Oskar Schlemmer (master of form) [e]

Paul Klee (master of form) [e]

Carl Schlemmer (foreman) [e]

Josef Albers (foreman) [e]

Wood sculpture:

Richard Engelmann (master of form) [e]

Johannes Itten (master of form) [e]

Georg Muche (master of form) [e]

Oskar Schlemmer (master of form) [e]

Hans Kämpfe (foreman) [e]

Josef Hartwig (foreman) [e]

Bauhaus pottery:

Leo Emmerich (foreman) [c]

Max Krehan (foreman)

Leibbrand (foreman) [d]

Gerhard Marcks (master of form)

[Photo: Detlef Gräfingholt, source: Bundesarchiv/ Wikimedia Commons, licence: CC BY-SA 3.0 de]

Metalworking:

Johannes Itten (master of form) [e]

Paul Klee (master of form) [e]

Oskar Schlemmer (master of form) [e]

Laszlo Moholy-Nagy (master of form) [e]

Marianne Brandt (teacher) [e]

Alfred Arndt (junior master) [e]

Lilly Reich (teacher) [e]

Naum Slutzky (foreman) [e]

Wilhelm Schabbon (foreman) [e]

Alfred Kopka (foreman) [e]

Christian Dell (foreman) [e]

Willi Wirths (foreman) [e]

Rudolf Schwarz (foreman) [e]

Alfred Schäfter (foreman) [e]

Paul Tobias (foreman) [e]

Furniture joinery:

Walter Gropius (master of form and Bauhaus director 1919-1928) [e]

Johannes Itten (master of form) [e]

Beck (teacher) [e]

Marcel Breuer (junior master) [e]

Josef Albers ( junior master) [e]

Alfred Arndt ( junior master) [e]

Lily Reich (teacher) [e]

Vogel (foreman) [e]

Josef Zachmann (foreman) [e]

Anton Handik (foreman) [e]

Erich Brendel (foreman) [e]

Reinhold Weidensee (foreman) [e]

Eberhard Schrammen (foreman) [e]

Heinrich Bökenheide (foreman) [e]

Script:

Dora Wibiral (master of form) [e]

Joost Schmidt ( junior master craftsman) [e]

Stone Sculpture:

Richard Engelmann (master of form) [e]

Johannes Itten (master of form) [e]

Oskar Schlemmer (master of form) [e]

Karl Krull (foreman) [e]

Max Krause (foreman) [e]

Josef Hartwig (foreman) [e]

Typography/ Advertising:

Herbert Bayer ( junior master craftsman) [e]

Joost Schmidt (Jungmeister) [e]

Willi Hauswald (foreman) [e]

Weaving:

Johannes Itten (master of form) [e]

Georg Muche (master of form) [e]

Anni Albers (teacher) [e]

Gunta Stölzl ( junior master craftswoman) [e]

Helene Börner (foreman) [e]

Mural painting:

Johannes Itten (master of form) [e]

Oskar Schlemmer (master of form) [e]

Wassily Kandinsky (master of form) [e]

Hinnerk Scheper ( junior master) [e]

Alfred Arndt ( junior master) [e]

Franz Heidelmann (foreman) [e]

Carl Schlemmer (foreman) [e]

Hermann Müller (foreman) [e]

Edwin Keiling ( foreman) [e]

List of Bauhaus students – apprentices and journeymen (not exhaustive)

Bookbindery:

Printing:

Stained glass:

Bauhaus pottery:

Theodor Bogler [a]

Werner Burri

Gertrud Coja [a]

Johannes Driesch [a]

Lydia Foucar [a]

Marguerite Friedlaender [a]

Thoma Gräfin Grote [b]

Margarete Heymann, née Heymann-Loebenstein [b]

Herbert Hübner [b]

Otto Lindig [a]

Wilhelm Löber [b]

Else Mögelin [a]

Eva Oberdieck-Deutschbein [b]

Renate Riedel [b]

Franz Rudolf Wildenhain [b]

Painting:

Otto Hofmann [a]

Metalworking:

Carpentry:

Wall painting:

Weaving:

Sources

[1] Förderkreis Keramik-Museum Bürgel e.V., Träger des Keramikmuseums Bürgel (ed.): Otto Lindig, Die Dornburger Zeit, Gera 2010, p. 8.

[2] Weber, Klaus (ed.): Keramik und Bauhaus, Berlin 1989, p. 10.

[3] Jakobson, Hans-Peter: Homage Otto Lindig, in: Wiss. Z. Hochsch. Archit. Bauwes. – A. – Weimar 36 (1990) 1-3, p. 142.

[4] Jakobson, Hans-Peter: Homage Otto Lindig, in: Wiss. Z. Hochsch. Archit. Bauwes. – A. – Weimar 36 (1990) 1-3, p. 142.

[5] Jakobson, Hans-Peter: Homage Otto Lindig, in: Wiss. Z. Hochsch. Archit. Bauwes. – A. – Weimar 36 (1990) 1-3, p. 142.

[6] Jakobson, Hans-Peter: Homage Otto Lindig, in: Wiss. Z. Hochsch. Archit. Bauwes. – A. – Weimar 36 (1990) 1-3, p. 142.

[7] Letter by Walter Gropius to Gerhard Marcks from April 5th 1923, quoted from: Weber, Klaus (ed.), Keramik und Bauhaus, Berlin 1989, p. 42.

[8] Weber, Klaus (ed.): Keramik und Bauhaus, Berlin 1989, p. 10.

[9] Weber, Klaus (ed.): Keramik und Bauhaus, Berlin 1989, p. 42.

[10] Weber, Klaus (ed.): Keramik und Bauhaus, Berlin 1989, p. 22-24.

[11] Jakobson, Hans-Peter: Homage Otto Lindig, in: Wiss. Z. Hochsch. Archit. Bauwes. – A. – Weimar 36 (1990) 1-3, p. 143.

[12] Jakobson, Hans-Peter: Homage Otto Lindig, in: Wiss. Z. Hochsch. Archit. Bauwes. – A. – Weimar 36 (1990) 1-3, p. 142.

[13] Weber, Klaus (ed.): Keramik und Bauhaus, Berlin 1989, p. 13.

[14] Weber, Klaus (ed.): Keramik und Bauhaus, Berlin 1989, p. 24-25.

[15] Gerhard Marcks: Otto Lindig, in: SIGILL Blätter für Buch und Kunst, booklet 1, sequence 6, Otto Rohse Presse, Hamburg 1977, pp. 21 f.

[16] Letter by Gerhard Marcks to Richard Fromme from February 8th 1925, quoted from: Weber, Klaus (ed.): Keramik und Bauhaus, Berlin 1989, pp. 42-43.

[17] Letter by Gerhard Marcks to Richard Fromme from February 8th 1925, quoted from: Weber, Klaus (ed.), Keramik und Bauhaus, Berlin 1989, p. 25.

[18] Letter by Gerhard Marcks to the Bauhaus from May 26th 1923, quoted from: Weber, Klaus (ed.), Keramik und Bauhaus, Berlin 1989, p. 41.

[19] Jakobson, Hans-Peter: Homage Otto Lindig, in: Wiss. Z. Hochsch. Archit. Bauwes. – A. – Weimar 36 (1990) 1-3, S. 143; Förderkreis Keramik-Museum Bürgel e.V., Träger des Keramikmuseums Bürgel (ed.): Otto Lindig, Die Dornburger Zeit, Gera 2010, p. 20; Jakobson, Hans-Peter: Otto Lindig: „Im Grunde ist das Töpfemachen ja immer die gleiche Sache…“, in: Weber, Klaus (ed.): Keramik und Bauhaus, Berlin 1989, p. 53.

[20] Letter by Brief Gerhard Marcks to Richard Fromme from June 6th 1921, quoted from: Weber, Klaus (ed.): Keramik und Bauhaus, Berlin 1989, p. 37.

[21] Gerhard Marcks quoted in: Weber, Klaus (ed.): Keramik und Bauhaus, Berlin 1989, p. 36.

[22] Letter by Gerhard Marcks to Walter Gropius from September 9th 1935, quoted from: Weber, Klaus (ed.): Keramik und Bauhaus, Berlin 1989, p. 36.

[23] Weber, Klaus (ed.): Keramik und Bauhaus, Berlin 1989, p. 42.

[24] Letter by Gerhard Marcks to the Bauhaus from February 2sd 1922, quoted from: Weber, Klaus (ed.), Keramik und Bauhaus, Berlin 1989, p. 42.

[25] Letter by Gerhard Marcks to Richard Fromme from February 8th 1925, quoted from: Weber, Klaus (ed.): Keramik und Bauhaus, Berlin 1989, p. 43.

[26] Weber, Klaus (ed.): Keramik und Bauhaus, Berlin 1989, p. 40.

[27] Weber, Klaus (ed.): Keramik und Bauhaus, Berlin 1989, p. 40.

[28] Otto Lindig, quoted from: Weber, Klaus (ed.), Keramik und Bauhaus, Berlin 1989, p. 39.

[29] Gerhard Marcks, zitiert aus: Weber, Klaus (ed.), Keramik und Bauhaus, Berlin 1989, p. 33.

[30] Förderkreis Keramik-Museum Bürgel e.V., Träger des Keramikmuseums Bürgel (ed.): Otto Lindig, Die Dornburger Zeit, Gera 2010, p. 22.

[31] Neurauter, Sebastian: Das Bauhaus und die Verwertungsrechte, Tübingen 2013, p. 311.

[a] Jakobson, Hans-Peter: Homage Otto Lindig, in: Wiss. Z. Hochsch. Archit. Bauwes. – A. – Weimar 36 (1990) 1-3, p. 142.

[b] Förderkreis Keramik-Museum Bürgel e.V., Träger des Keramikmuseums Bürgel (ed.): Otto Lindig, Die Dornburger Zeit, Gera 2010, p. 45.

[c] Weber, Klaus (ed.): Keramik und Bauhaus, Berlin 1989, p. 10.

[d] Weber, Klaus (ed.): Keramik und Bauhaus, Berlin 1989, p. 11.

[e] Siebenbrodt, Michael/ Schöbe, Lutz: Bauhaus, 1919-1933 Weimar-Dessau-Berlin, New York 2012, pp. 250 f.

Other sources:

Museen der Stadt Gera u.a. (ed.): Otto Lindig der Töpfer, Gera/ Karlsruhe 1990, pp. 9-12.

Neumann, Eckhard (ed.): Bauhaus und Bauhäusler, Köln 1985, p. 12.

Weber, Klaus (ed.): Keramik und Bauhaus, Berlin 1989, pp. 10, 27.

Bauhaus Pottery Works

Showing all 5 results

-

HET KRUIKJE (Marguerite FRIEDLAENDER-WILDENHAIN) [attributed] – Two Cups with Saucers in Bauhaus Style – Studio Pottery

680,00 €incl. shipping

Delivery time: 7-14 days

Add to cart -

HET KRUIKJE (Marguerite FRIEDLAENDER-WILDENHAIN) [attributed] – Milk Jug with Gintsugi-Restoration – Studio Pottery

380,00 €incl. shipping

Delivery time: 7-14 days

Add to cart -

Johannes LEẞMANN (* 1903, † 1944) – Vase in Bauhaus Style – Studio Pottery

480,00 €incl. shipping

Delivery time: 7-14 days

Add to cart -

Otto LINDIG (* 1895, † 1966) – Vase with Lava Glaze – Studio Pottery

1 480,00 €incl. shipping

Delivery time: 7-14 days

Add to cart -

Otto LINDIG (* 1895, † 1966) [attributed] – Bauhaus Pottery Vase (sphere)

680,00 €incl. shipping

Delivery time: 7-14 days

Add to cart

Showing all 5 results